Despite the increasing demand for raw materials, mining in the deep sea remains controversial.

Mining in the deep sea is a highly controversial and complex subject: fears that it will have devastating consequences for marine life are offset by growing demand for raw materials, which companies believe can only be met by developing subsea deposits. The member states of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) held intensive discussions during three weeks of negotiations in July in Jamaica’s capital Kingston. However, the ISA, the UN body overseeing mining, could not agree on concrete ocean resource extraction regulations at the meeting. Further votes were postponed until next July’s ISA meeting.

Nauru as a Precedent for Large-Scale Deep-Sea-Mining?

The issue became the focus not only of the debates in Kingston but also of media coverage due to the case of the South Pacific island of Nauru. The small island nation would like to provide financial resources to pursue mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) with the help of the Canada-based “The Metals Company” (TMC). Since the CCZ is in international waters, a resource mining permit from the ISA is required. Nauru’s June 2021 application to mine minerals in this zone triggered the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea’s two-year permit period clause for the maritime authority. By July 2023, the ISA should have established a set of rules against which to decide Nauru’s application and future requests from other countries for ocean resource extraction. The ISA said that no agreement was reached at the July meeting, so the legal framework and guidance on mineral extraction had not been fully worked out.

The CCZ – A Resource-Rich Zone in the Middle of the Pacific Ocean

The CCZ between Hawaii and Mexico. – Photo: USGS (U.S. Geological Survey).

The CCZ is a deep-sea area located between Mexico and Hawaii, slightly larger than the European Union, and is home to rich deposits of manganese nodules. These are in demand because they contain minerals like copper, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements.

A manganese tuber removed from the CCZ. – Photo: iStock/Bjoern Wylezich.

The black-brown nodules, which average between one and 15 centimeters in size, form primarily at ocean depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters over several million years and contain not only the eponymous manganese but other sought-after minerals as well.

The decision in the case of the island nation could have far-reaching consequences for mining in the deep sea. Currently, mineral resources in the oceans are primarily mined for research purposes and not yet on a large, industrial scale. There are currently 31 exploration contracts that the ISA has awarded to companies. These are financially supported by countries such as China, Russia, France, and Japan. Nineteen of these exploration licenses alone, which are valid for a period of 15 years, treat the exploration of manganese nodules.

In recent months and years, marine researchers, environmental organizations, companies, and governments have voiced their various points of view and concerns, both for and against mineral extraction in the depths of the ocean. We have compiled some of them below.

Far-Reaching Effects on Ecosystems, Too Little Research

Criticism of deep-sea mining is primarily concerned with the wide-ranging consequences on marine life, whose existence would be permanently disrupted, as reported by the German Max Planck Society (document in German). This finding is based on recent research on an area where a few kilometers of the seabed were plowed up with a harrow in 1989 as a test to replicate manganese nodule mining. The mineral extraction process itself stirs up sediment as the top few inches of the seafloor – and the life within it, is removed. Twenty-six years later, the plow marks were still clearly visible. In their investigations, the Max Planck Society researchers found that, in some cases, only half the bacteria still lived in the soil of the old tracks compared to the untouched seafloor and expect that these microorganisms will not be able to fully perform their natural functions again for at least 50 years. The director of the German Senckenberg Institute by the Sea, Pedro Martinez Arbizu, also noted that manganese nodule removal caused sponges or corals that live directly on the nodules to disappear. This is particularly concerning considering that manganese nodules grow extremely slowly, only between two and 100 millimeters in a million years. Mining in the oceans would therefore have an enormous impact on biodiversity.

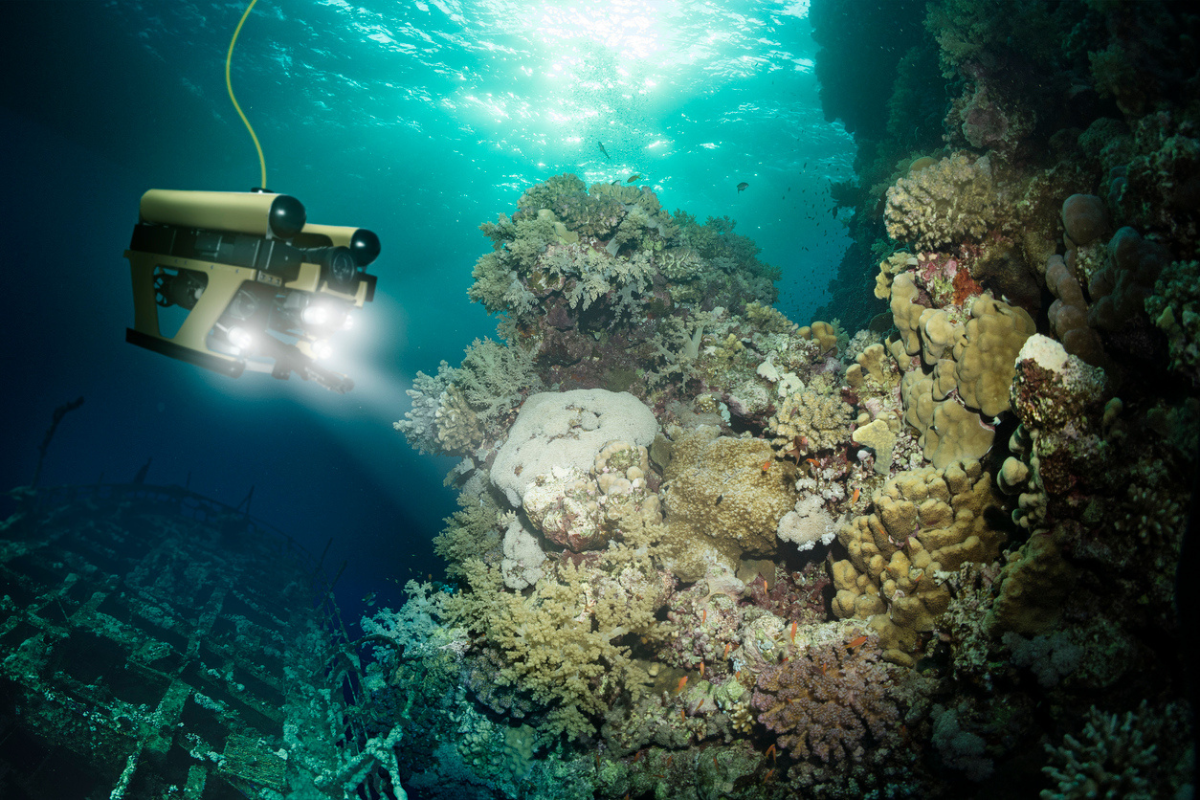

Coral reef with an orange sponge in the depths of the sea. – Photo: iStock/mychadre77.

A study by a group of scientists published in the science journal Nature npj Ocean Sustainability concludes that rising ocean temperatures caused by climate change could encourage tuna to migrate to the Clarion-Clipperton zone – and thus to the site where deep-sea mining is planned. This would affect fish life and, ultimately, the fishing industry in the Pacific. Other aspects, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), are the noise and light pollution that could be caused by mining machinery and ships used for mineral extraction. There is also a risk that leaks or fuel spills could release environmental toxins into the seawater, which in turn could threaten various animal species, warns the IUCN.

Another body that has expressed concerns about deep-sea mining is the international conservation organization Fauna & Flora. It published a report showing how strongly the marine ecosystem would be affected by deep-sea mining: Biodiversity in the oceans would be lost – and irretrievably so. But carbon stores in sediments would also be disturbed, disrupting carbon cycles and storage processes, which could exacerbate the climate crisis. The study adds that marine sediments are among the world’s largest and most important CO2 reservoirs, so their protection is critical. However, the extent of the impact of the climate crisis is not yet known, the research concludes. Fauna & Flora’s director of global policy, Catherine Weller, therefore also asked the ISA in the negotiations in Kingston not to issue any further mining permits for the time being and instead to adopt a moratorium. Sophie Benbow, Director of Marine Research, also warned that “deep-seabed mining and its effects may be impossible to stop” once started.

Tuna in the ocean – Photo: iStock/Nuture.

Impacts not Only on Marine Life but Also Land

In addition to the IUCN and Fauna & Flora, before the meeting in Jamaica, several countries spoke in favor of a break or postponement of the deadline in case of a decision on Nauru’s concerns due to environmental concerns. The number of pro-moratorium countries grew to 21 during the multi-week meeting. Among them are Germany and Canada. France went a step further: President Emmanuel Macron had already called for a ban on such activities in June 2022 – but his country is so far alone in this position. A government spokesman for the United Kingdom, which is not on the list of countries for a moratorium or ban, told the BBC that his country would not support licensing until there was enough research on the impact on ecosystems. After all, the depths of the oceans are considered the least explored part of the earth, and numerous creatures that live there are still unknown. In an interview with the German journal Süddeutsche Zeitung, Pedro Martinez Arbizu also questioned whether it was possible to evaluate where destruction would be more morally justifiable: on land or at sea. He also stressed that “humanity leaves a huge footprint on the Earth.” [Translation rawmaterials.net].

“France supports the ban on any exploitation of the deep seabed.” [Translation Rawmaterials.net].

Emmanuel Macron on the 7th of November 2020 via Twitter.

Not only have consequences for the ecosystem and the animal and plant world been raised. Possible effects on human health are also conceivable. According to researchers at the German Alfred-Wegener-Institut, manganese nodules are radioactive. Much more than previously assumed. The presence of radioactive substances led to the cancellation of mining projects in the past – for example, at Greenland’s Kvanefjeld mine, where uranium concentrations exceed local limits (we reported).

“We know less about the deep sea than any other place on the planet […] What we do know, however, is that the ocean plays a critical role in the basic functioning of our planet, and protecting its delicate ecosystem is, therefore, not just critical for marine biodiversity, but for all life of the earth.”, Sophie Benbow raises concerns.

In the meantime, the effects of deep-sea mining are coming into focus not only among environmental organizations and governments but also among companies. In 2021, Samsung SDI, Google, and Volvo signed a moratorium on deep-sea mining initiated by the non-governmental organization WWF and the BMW Group. These companies thereby commit to neither purchase raw materials mined in the oceans nor use them in their supply chains and to not finance any mining activities in the ocean depths. The WWF (World Wide Fund For Nature) refers to deep-sea mining as an “avoidable environmental disaster.” The organization appeals to other companies to join the moratorium and calls for deep-sea mining not to be carried out until all possible risks can be researched, alternatives to it exhausted, and – in the case of mining – marine ecosystems adequately protected. WWF urges that instead of mining in the oceans, the focus should be on new ideas on land to minimize the consequences for the population and the environment.

In addition to the impacts on marine and land dwellers, there are also number-driven factors: according to Reuters, voices have been raised that put forward financial risks and uncertain economics as arguments against investing in ocean exploration. There are many big unknowns here: Some costs could not be estimated, according to a study involving the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR). Because extensive processing of manganese nodules is not currently being done, it isn’t easy to forecast the processing costs. Other factors, such as the fees to the ISA for the license received, are entirely unknown. Profitability is, therefore, questionable. A study conducted on behalf of the ISA concludes that deep-sea mining is not yet profitable at current commodity prices. However, the price level is expected to rise in the next 15 to 40 years due to the increasing demand for minerals needed for renewable energies, which could make mining in the ocean depths profitable in the long term. So it is time to devote even more attention to this research topic.

Traditional mining in an onshore mine with a visible impact on the environment. – Photo: iStock/zhuzhu.

Raw Materials From the Deep Sea Necessary for the Energy Turnaround?

On the side of the proponents of deep-sea mining, on the other hand, the argument is made that the minerals to be extracted in international waters are essential for achieving global climate goals. This point was made, among others, by the Canadian deep-sea mining specialist “The Metals Company” (TMC), which in addition to Nauru, has entered into partnerships with two other Pacific islands and would like to accelerate the approval of applications for mineral mining – thus, of course, pursuing its interests. There are, however, dissenting voices to this viewpoint, saying that deep-sea mining is not necessary for either the energy or transportation transition. For example, Andreas Manhart of the Öko-Institut in Freiberg, Germany, together with other scientists, found in a study commissioned by Greenpeace that manganese nodules do not contain the minerals lithium and graphite, which are essential for alternative energy production. Only manganese, cobalt, and nickel could be extracted in larger quantities through deep-seabed mining, the study continues. Other researchers come to the same conclusion and offer an alternative proposal: first, expand the potential of the circular economy and focus more on the recycling of critical minerals instead of expanding mining from land to the depths of the world’s oceans.

TMC wants to extract copper, cobalt, and nickel from the seabed, which is needed for electric mobility, wind turbines, and cell phones, among other things. One of the reasons given by the company for this is that easily accessible metals have already been mined on land, and the raw materials now remaining there would be of low quality. This is an argument that the Swedish state-owned mining company LKAB will surely disagree with. Earlier this year, it announced the discovery of a huge deposit of rare earths that is also rich in iron and phosphorus. Other countries such as Tanzania are also working hard to develop deposits of critical minerals, and secondary sources such as mining residues are also gaining importance because of recent research.

The Canadian company TMC also bases its assessments on research that concludes that the climate impact of onshore mining would be significantly higher than that of deep-sea mining. The TMC has devoted only limited attention to the impact on the marine ecosystem and has not yet been able to deliver definitive results, but says it is continuing its research. However, during the ISA negotiations in Jamaica, Canada, the company’s headquarters also called for a halt to deep-sea mineral mining permits.

Another argument favoring mining in the oceans is that minerals difficult to reach on land would be much easier to extract in the sea – at least theoretically. Wood Mackenzie’s research director for global mining, Nick Pickens, argued to the BBC that while the raw materials available on land would be in large quantities, they would not be as easily accessible due to conflicts such as those in the copper-rich Democratic Republic of Congo; refining facilities would also be limited to a few locations. He indicated that mining minerals would not necessarily eliminate geopolitical challenges in the deep sea.

U.S. Position: At a Disadvantage as a Non-Member of the ISA?

However, one of the largest mining nations cannot be left out of this debate: The United States. It has not yet joined the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (short UNCLOS), which created the legal basis for establishing the ISA. Nevertheless, they regard the Law of the Sea as an expression of customary international law and practice. Nevertheless, the question remains whether non-ratification puts the major economic power in a privileged or disadvantageous position; the legal interpretation raises questions and leaves some room for maneuver, which is why it has already been the subject of academic research.

Although representatives of governments, organizations, and various industries in the U.S. have advocated U.S. accession several times, it has not yet received the necessary approval from the U.S. Congress. Among the advocates are high-ranking American politicians such as former President Barack Obama and John Kerry during his time as U.S. Secretary of State (now Special Envoy for Climate Protection), as well as former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton: they all spoke out in favor of signing UNCLOS during their respective terms in office.

Joining UNCLOS, and thus the ISA, could benefit the United States: The Senate Foreign Relations Committee pointed out that the North American country would gain more than any other country from the treaty in terms of economy, security, and international influence.

“Non-membership,” on the other hand, could have a negative impact, advocates say. National Association of Manufacturers CEO and President Jay Timmons argued that it would be disadvantageous for U.S. companies to invest in deep-sea mining because they could not obtain legal title until the U.S. is part of UNCLOS or the ISA. Foreign companies whose governments have joined could be at an advantage here and receive permission to engage in deep-sea mining. Timmons made the case for signing the Law of the Sea Convention in 2012.

Concerns were also raised that, if a mining license were granted to Nauru, mining could occur in deep-sea areas bordering the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The EEZ is an area that extends a maximum of 200 nautical miles from a country’s shores and borders the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. Any coastal nation can claim it. In the respective EEZ, countries have sovereign rights and can also exploit seabed resources there, such as deep-sea mining. The United States has one of the largest EEZs in the world. The environmental and legal organization Earthjustice fears deep-sea mining in the CCZ poses a “significant risk” to islands like Hawaii or Guam located on U.S. territory and directly neighboring areas where Nauru wants to extract raw materials from the oceans. The non-governmental organization, therefore, turned to U.S. President Joe Biden after Nauru’s 2021 request, asking him to commit the administration to a moratorium not only in the EEZ but also in the CCZ administered by the ISA.

The U. S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). – Photo: Courtesy of NOAA.

In addition to numerous member states of the ISA, there are also efforts in the USA to obtain a moratorium on deep-sea mining. At the start of the ISA conference this July, U.S. Congressman Ed Case called for deep-sea mining to be stopped for the time being until the effects were sufficiently known and protective measures for the oceans were established and introduced a corresponding bill.

Despite all Skepticism: Could Deep-Sea Mining Start as Early as 2025?

In addition to efforts to extract raw materials in international waters, there are already plans to tackle deep-sea mining in national waters, which does not require approval from the ISA. In June, for example, it became known that Norway would like to enable deep-sea mining in its territories (we reported).

Whether an agreement can be reached at the upcoming ISA negotiations in July 2024 remains to be seen. Deep-sea mining in international waters will likely be put on hold until then. TMC announced after the negotiations in Kingston that it intends to apply an exploration contract to the ISA following the July 2024 meeting. The company aims to start production in the fourth quarter of 2025 with the support of the Nauru government, as it anticipates a year of negotiations with the ISA. By then, however, other companies could be added to the list submitting mining applications for resource extraction in international waters, and the U.S. could also decide to ratify the Law of the Sea Convention after all. It is also likely that ongoing research into the impacts of mining – including on marine ecosystems – will continue at full speed until July, to conclude it as soon as possible. In any case, there will not be much time before the ISA meeting in 2024 to come up with well-founded, decisive arguments and research results for or against the start of deep-sea mining.

Photo: iStock/S_Bachstroem